Where We Work

See our interactive map

Midwives and nurses—like Sellyvine (left) at the women's hospital in Nakuru, Kenya—make up 50% of the health workforce worldwide. They're in the spotlight during 2020 and will play a crucial role in whether their countries can achieve their most ambitious health targets by 2030. Photo by Georgina Goodwin for IntraHealth International.

We have a lot to do before 2030, if we're going to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

Every year, we look at the top global health issues coming our way in the next 12 months. But global health is a long game and it’s a brand-new decade, so this year, we’re looking ahead to the coming 10 years.

From coronavirus to digital health to climate change, here are 10 of the global health issues that we at IntraHealth International will be watching in the decade to come.

In 2018, Bill Gates told Business Insider that a coming disease—maybe one like the 1918 flu—could kill 30 million people within six months, and that countries should prepare for it like they would for war.

Coronavirus—now officially known as COVID-19—likely won’t be as disastrous as that particular prediction, but there have been 45,171 confirmed cases globally across two dozen countries, and 1,115 people have died. It has global health officials very concerned about just how prepared we are for this or any other pandemic. On January 31, 2020, the World Health Organization declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.

Health workers carry huge responsibility and huge risk.

Health workers like Li Wenliang—who died from coronavirus just two months after he tried to warn the world about a SARS-like illness in Wuhan, China—and Sheik Umar Khan—a Sierra Leonean physician who died of Ebola in the same hospital where, just weeks before, he’d been treating Ebola patients—are on the front lines of any infectious disease outbreak, from measles to meningitis to polio.

They carry huge responsibility and huge risk. In one Wuhan hospital, a single patient infected at least ten health workers and four other patients, according to the New York Times.

That’s one reason the Frontline Health Workers Coalition is advocating for more support for frontline health worker teams, not only as they fight this outbreak but also as a focused investment in resilient, sustainable, locally led health systems that can respond to infectious disease outbreaks.

Read: Frontline Health Workers Must Be a Priority in Coronavirus Response

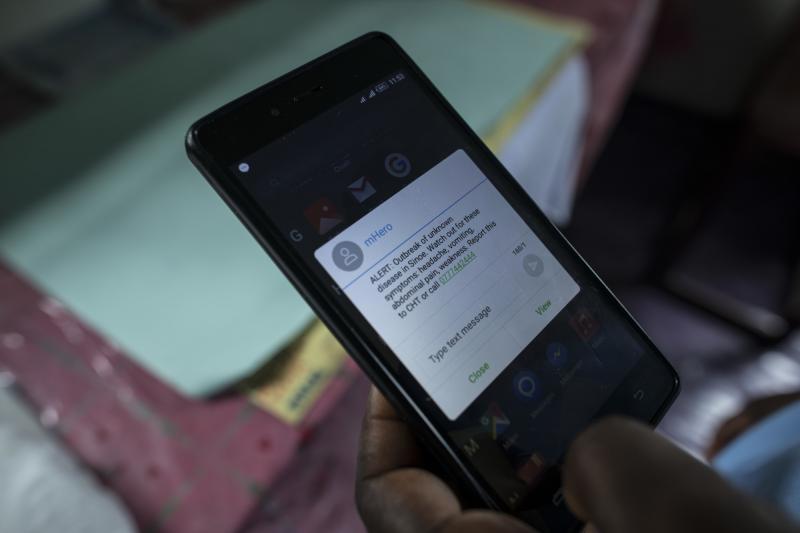

mHero—a system that uses basic text messaging to connect ministries of health and health workers—was designed during West Africa's 2014 Ebola outbreak. Communication and accurate information are key during any outbreak. Photo: Sarah Grile for USAID

Whether we call it fake news, pseudoscience, censorship, or spin—misinformation is responsible for far too many lives cut short. Online misinformation in particular can fuel epidemics, including tooth decay, measles, polio, Ebola, and, now, coronavirus.

There’s even a word for it: misinfodemics.

Not only does misinformation spread disease, it spreads mistrust. This can have disastrous consequences for frontline health workers and journalists, including derailing their efforts to curb and report on outbreaks—and much worse.

In the coming decade, how we present and consume information online will have a direct impact on global health—not just for humans, but for wildlife, plant life, and the environment we share.

The 2010s were the hottest decade on record. Not just on land, but also at sea, where 90% of excess heat from greenhouse gases is stored.

Rising temperatures can change everything. Our water quality, our air quality, the quality and quantity of our food crops around the world. They intensify heatwaves and storms, leading to floods and wildfires. In fact, UK scientists say that wildfires like the ones Australia is battling—which have burned 11 million hectares and killed 33 people, tens of thousands of farm animals, and countless plants and wildlife—will become the norm.

Health workers will see climate consequences in their clinic waiting rooms.

In the coming decade, more and more frontline health workers will see the consequences of our changing climate in their clinic waiting rooms. They’ll need to be ready to address the effects of hunger from failing crops, chronic respiratory diseases caused by air pollution, and all the health challenges that come with human displacement due to catastrophic weather.

During the first week of the coronavirus outbreak in China, health workers from eight hospitals in the Hubei Province, where the city of Wuhan is located, put out an urgent call for medical supplies—specifically surgical masks, goggles, and gowns, according to a report by the New York Times.

“There are no beds, no resources,” a nurse said in an interview with CNN. “Are we supposed to just fight this battle bare-handed?”

If we’re going to achieve universal health coverage in the coming decade, supply chain management will be more crucial than ever.

“No health program can succeed if the medicines and health products people need aren’t available when and where they need them,” write IntraHealth’s Batouo Souare and Melanie Joiner. Without qualified, well-trained human resources to manage supply chains, we can’t make sure health products are available, either day-to-day or during emergencies.

A supply chain worker moves health supplies in a warehouse in Senegal. Photo by Clement Tardif for IntraHealth International.

Read: Trained Supply Chain Workers Are Key to Improving Access to Health Products at Senegal's Last Mile

“It’s been ten years since the first truly affordable smartphone was introduced and unleashed a transformation across the African continent,” says Wayan Vota, IntraHealth’s director of digital health. “These days, over 40% of all Africans use smartphones, and the technology generates 8.6% of GDP in sub-Saharan Africa. But the tech transformation hasn’t stopped with telecommunications. The field of digital health has expanded, too.”

Read: These 10 Trends will Define Digital Health in the Next Decade

In the coming decade, he says, health workers and officials around the world are going to get more sophisticated in the way they collect, share, and analyze data. From advanced image processing algorithms that diagnose cancer and eye diseases to chatbots that detect depression in real time—digital health tech and its users will have to keep up with all-new issues around data security, machine learning, and using data to solve some of our biggest disease challenges.

Data clerk Erastus Angula inputs client information at his health facility in Omuthiya, Namibia. Photo by Morgana Wingard for IntraHealth International

In the US, Time reports, suicide rates are the highest they’ve been since World War II. A study published in Pediatrics in November 2019 found that the rate of suicide attempts for black youths in the US rose 73% from 1991 to 2017.

Seventy-three percent.

And according to the World Health Organization, between 76% and 85% of people with mental disorders in low- and middle-income countries receive no treatment for their disorders, including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, dementia, substance abuse, and developmental disorders.

We can’t go on pretending that a tidal wave of need isn’t going unmet.

South Sudan, for example, “will have a tremendous need for mental health services in the post-conflict era,” says Anne Kinuthia, IntraHealth’s country director in South Sudan, where violence has left 4.3 million people displaced. “But we don’t have the systems or workforce in place in this country to manage mental health. We see people tied to their hospital beds or locked up at home. If we want to see healthy societies, people with mental health needs will need support, too.”

Read: The Future of HIV Care in South Sudan Starts Here

Today around 70% of all cancer deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries.

As people all over the world live longer than ever, this and other noncommunicable diseases—including obesity-related illnesses, hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, and mental illness—have become the leading cause of death and disability worldwide.

“When I was starting out as a young doctor here in Senegal, noncommunicable diseases were thought to be a thing for rich people,” says Joseph Barboza, a physician in Senegal and director of IntraHealth International’s work on Better Hearts Better Cities Dakar. “It used to be infectious diseases like measles, malaria, and meningitis that brought people to the emergency room. Now most of those emergencies are caused by NCDs, usually hypertension. In some cities, the prevalence is as high as 40%.”

In the coming decade, countries will need resilient health systems and strong health workforces to meet this challenge.

Read: Door-to-Door Hypertension Care in Dakar Brings a Pervasive Public Health Problem to Light

Nurses, midwives, doctors, pharmacists, lab workers, clinical officers—the range of jobs and responsibilities within the health workforce is vast. And each one is crucial.

The 2020s are starting off with a focus on nurses and midwives. And rightly so—they make up 50% of the health workforce worldwide. As we get closer to our most ambitious global goals—nothing short of universal health coverage, an AIDS-free generation, and the end of extreme poverty—the global community has realized that nurses and midwives will be the ones to get us there. That’s one reason the WHO declared 2020 to be the Year of the Nurse and the Midwife.

But to make real progress, the health workforce needs need more nurses and midwives at the top. Which brings us to:

Women make up 70% of the total health and social care workforce and an even larger share of the nursing and midwifery profession, yet they occupy only 25% of health system leadership roles.

One of the many reasons, according to the 2019 report Investing in the Power of Nurse Leadership: What Will It Take?, is that women, more so than men, must juggle paid and unpaid work, managing jobs and home life at the same time. Case in point:

“I remember once, I found a four-week-old baby sleeping on the floor in a corner of the nurses’ office,” writes Tembi Mugore, a midwife and senior advisor for health sector performance and sustainability at IntraHealth. “When I asked whose baby it was, the nurse-midwife, who was busy providing antenatal care at the same time, responded, “She is my baby. I could not stay on maternity leave for long because I am the only nurse-midwife at this clinic. This community relies on me.”

Read: Reflections on 2020 from a Nurse and a Midwife

“It’s clear this isn’t about the individual nurse who needs to be developed,” said IntraHealth’s Constance Newman at the report’s launch event at Women Deliver 2019. “It’s about the systems that need to be changed in order to raise the profile and improve the status and effectiveness of nurse leaders.”

In the coming decade, we’ll be pushing for greater global progress toward gender equity, in the health workforce and beyond.

We have a lot to do before 2030 if we’re going to get close to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

We want to achieve an AIDS-free generation. Family planning for all who need it. Universal health coverage. Gender equality in health care. An end to maternal and child deaths. And solutions for the 70.8 million people who have now been forcibly displaced from their homes due to war and other disasters.

In the coming decade, we’ll be monitoring and pushing for progress on all these fronts—working hard to build the future we want.

Read more:

Get the latest updates from the blog and eNews