Where We Work

See our interactive map

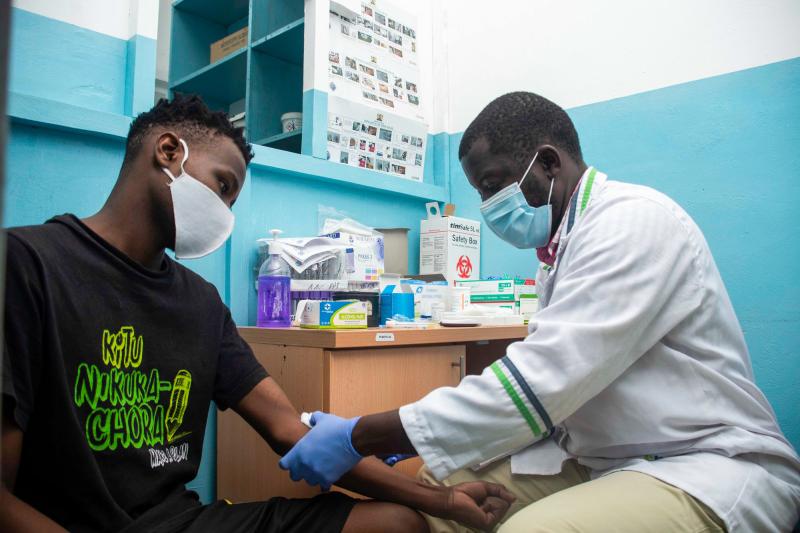

Nicodemas Ondies, medical lab officer at Tudor Subcounty Hospital in Mombasa County, Kenya takes samples from a client. Photo by Edwin Joe for IntraHealth International.

These strategies can help mitigate the projected health worker shortage.

As 2022 ends, the world is reflecting on and trying to recover from the third year of an ongoing pandemic. The road to recovery is long and made even more difficult by the massive shortage of what drives health systems: the health worker.

Last week, this shortage was on the agenda at a high-level summit with African heads of state, sponsored by the White House. While the US made clear it would work closely on this issue with African partners, it did not commit to working with Congress to secure any new funding to alleviate the crisis. Nor did any African leaders come forward with specifics on their own investments.

It’s time to go beyond rhetoric to real action.

It’s time to go beyond rhetoric to real action. By 2030, the World Health Organization projects a global shortage of 10 million health workers. This compromises efforts to achieve universal health coverage. Sub-Saharan Africa in particular suffers from the shortage—many countries have only 35% of the required doctors, nurses, and midwives the World Health Organization recommends to meet the population’s needs.

This shortage is, in part, fueled by massive brain drain from sub-Saharan Africa to the West. While wealthier nations actively recruit health workers from Africa to fill their own staffing shortages, countries such as Nigeria and Zimbabwe have seen an increase in the migration of physicians, nurses, midwives, and other health professionals. Within countries in the region, there are stark disparities in the proportion of health workers willing to work in rural and lower-income communities where the health burden is often greatest.

The knowledge lost when a community health worker (CHW) or highly trained medical expert leaves can have a long-term impact on the community.We are part of the community of health workers who were proudly trained in our native countries, where we hoped to stay and provide clinical care in our communities.

We are acutely aware of the painful decisions some of us have had to make in leaving the continent to seek better opportunities elsewhere, and the cumbersome administrative processes and financial costs required in the immigration processes.Some health workers choose to stay in the region, but they face massive challenges:

Although many governments are now scaling up CHW programs to minimize this gap, achieve universal health coverage, and ensure they are prepared for future public health emergencies, most of these programs are donor-funded and thus unsustainable for the long term. There are six times more voluntary CHWs than paid CHWs working in sub-Saharan Africa national CHW programs.

Initiatives such as the Biden-Harris Administration Global Health Worker Initiative and the African Union Health Workforce Task Team (AU-HWTT) are laudable efforts—with enough political will, they could help mobilize national and donor resources while charting a centralized long-term strategy to train and retain health workers. The African Union’s leadership is particularly critical to maximize economies of scale across the continent.

As the specifics of these initiatives are being worked out, we urge global health leaders to adopt four strategies that we believe can help us rebuild faster and reduce the projected gap in 2030 and beyond:

This is a key component to retaining the current and future health workforce. Many health worker strikes in Africa are due to inadequate and untimely pay by their governments.

Fair remuneration goes beyond basic salary and allowances and should account for housing, access to water, electricity, access to high-quality health services, and high-quality educational and employment opportunities for health workers’ families.Many health worker-focused projects look to increase access to health training institutions in more rural locations to boost enrollment from these communities. But without well-structured compensation plans and career progression pathways, graduates face the temptation to migrate to cities and other countries to maximize their earning potential. Multisectoral coordination is required to think through how to incentivize health workers to serve in all communities.

The effort to increase production of health workers via medical education will likely be country-specific but should be aligned with a broader African vision and strategy. AU-HWTT must define and build the political will to implement training institution accreditation standards, regional and sub-regional education curricula, and competencies.

This is particularly important for preservice training, during postgraduation internships, and for continuing medical education. Curricula with unified competencies will help equip health workers with the skills to provide contextually relevant care within their countries and across the region.

Harmonized health worker compensation scales for the whole region (with the flexibility to adjust for purchasing power in each country and to account for posting to rural or hardship locations) could support flexible deployment (short-term postings to meet acute needs and training exchanges to meet longer-term needs), and migration of health workers within the region.

As part of a coordinated regional strategy to assess human resources gaps and project future needs,

leaders of these initiatives should explore creative approaches to leverage the extensive network of Africans in the diaspora to support health worker education and training in their member states. Many specialist health workers travel for postgraduate training and eventually migrate. Institutions on the continent should be able to provide the infrastructure and mentoring necessary to provide high-quality specialist training for physician, nurse, and midwife cadres and support their practice.And while we endeavor to expand access to primary health care and universal health coverage, we must simultaneously expand access to lifesaving surgical care (a current gap on the continent) and other specialist interventions that are routinely available in wealthier countries.

COVID-19 highlighted their accessibility to the general public, but research has documented their role as the first point of care for clients who have common primary health care conditions. They are nimble and present in hard-to-reach areas and they are trusted in their communities.

Community pharmacies already operate a for-profit model. Examining how they can be integrated as frontline workers—and reliably connected to CHWs and the primary level of the health system—would allow country governments to leverage their skills and accessibility to reach people, to act as local public health surveillance workers, and to provide a regulatory and administrative framework to improve the quality of care they currently provide.

To coordinate these increased training efforts, we need strong mechanisms—such as iHRIS, developed and supported by IntraHealth International and recommended by the World Health Organization—to track and manage all health workforce data.

There is no health system without health workers.

Building the health workforce is possible but will require an all-hands-on-deck approach.

As we build momentum toward a bigger, stronger health workforce in 2030 and beyond, governments and advocacy organizations must remember to include health workers in every phase of the conversation. After all, there is no health system without health workers.Want to get more content like this delivered to your inbox? Sign up for our mailing list.

Get the latest updates from the blog and eNews