Where We Work

See our interactive map

This post originally appeared on AM Rounds.

Not so long ago, I retired from the practice of cardiology and clinical teaching in the US. I’m now serving as a volunteer in the Global Health Service Partnership (GHSP), which aims to bring faculty to medical and nursing schools in resource-limited settings globally. (Mullan and Kerry describe the GHSP in their recently published article.)

My post is a large national medical school in Tanzania, where I have been teaching internal medicine and cardiology for the past year.

The enormity of the medical education crisis in Tanzania is hard to fathom. After almost a year, I am just beginning to get my head around it.

So how do you provide medical education without faculty? Not very well, it turns out.

The current crisis can be traced to 1994 when a public sector hiring freeze, part of a program of retrenchment at the behest of the World Bank, was initiated. The Ministry of Health and Social Welfare reports that the number of health care workers fell from 23 per 10,000 people in 1994 to 6 per 10,000 in 2006. This hiring freeze, only now being slowly lifted, decimated the ranks of medical and nursing school faculty. In essence an entire generation of medical educators and administrators was lost.

Most schools report that they are functioning with 40-50% of the staff needed to provide instruction at the most basic levels. Our medical school has an enrollment of just over 1,200 undergraduate students spread over six years. As a part of a larger plan to meet the Millennium Development Goals, class sizes will increase by about 50% over the next three to five years.

No corresponding plan to increase the number of faculty exists.

So how do you provide medical education without faculty? Not very well it turns out. Basic science and introductory clinical medicine modules can be covered by traditional lectures.

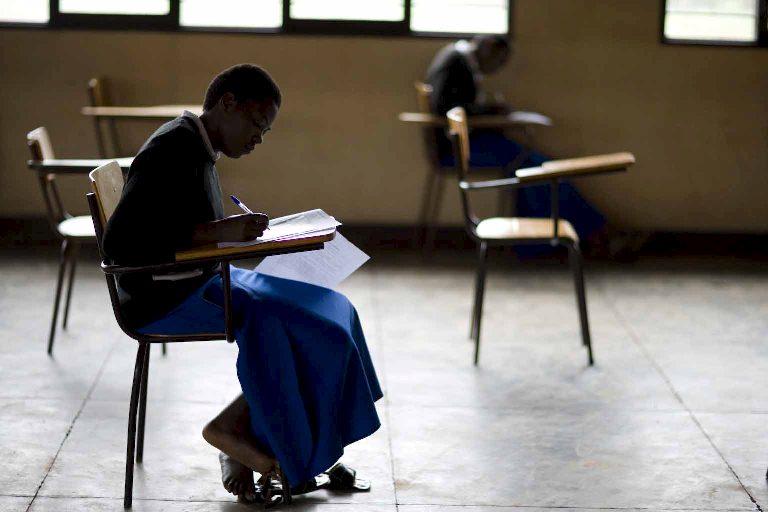

But, beginning in the 5th year, undergraduate students must become their own faculty. They are provided with a curriculum of seminars covering core subjects, which they then teach to themselves. When possible, instructors attend these seminars as tutors.

Clinical work on the wards is largely unsupervised except for occasional case presentations to instructors and unstructured work with registrars and house staff. Faculty only appear on the wards twice weekly to participate in teaching rounds. This pattern continues into the post-graduate years, where its effects are catastrophic. The predictable result is a graduate trained in theory but inexperienced and uncomfortable with the intricacies of daily patient management.

It is tempting to be critical of these practices, but once you’ve lived it for a while you realize that with so few faculty there are not many other options.

Improvement of medical education in resource-limited environments does not lend itself to narrowly targeted, disease-specific interventions which can be planned to fit budget cycles or development goals defined only by numbers of graduating students. Until the number of faculty can be increased to adequate levels, the current pattern of ineffective medical education will continue. Innovative programs like the GHSP have correctly analyzed the core issues and are exactly on target.

Photo by Charles Harris.

Get the latest updates from the blog and eNews