Where We Work

See our interactive map

Imelda Ngonyani is a skilled nurse in Tanzania. Photo by Josh Estey for IntraHealth International.

You can usually find nurse Imelda Ngonyani working in the maternity ward at Sekou Toure Regional Hospital in Mwanza, Tanzania.

“My happiest moments there are when I help a mom bring home a new, healthy baby,” she says.

Although she’s primarily helping women safely deliver, she’s also often called to a nearby clinic to perform a simple surgery for men that can help prevent HIV.

The voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC for short) clinic is just a walk away for Imelda, on the other side of the hospital. “About eight clients come in each day to have the procedure, and I attend to about three of them,” she says.

When clients arrive at the VMMC clinic at Sekou Toure Regional Hospital in Mwanza, Tanzania, nurse Flora Kyenche educates them on the procedure. Photo by Josh Estey for IntraHealth International.

For IntraHealth’s ToharaPlus project, VMMC is part of a comprehensive HIV-prevention package that also includes condom use, HIV counseling and testing, and referral for antiretroviral treatment when needed. Photo by Josh Estey for IntraHealth International.

Nurse Flora gives clients condoms and stresses the importance of using one every time they have sex to better protect themselves from HIV. Photo by Josh Estey for IntraHealth International.

Nineteen-year-old Emanueli Somweli is one of the clients Imelda is helping today. He heard about VMMC from public service announcements in his hometown.

“My parents encouraged me to come in,” he says. “I think this service will help protect me from HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.”

Medical male circumcision reduces a man’s risk of acquiring HIV through heterosexual intercourse by approximately 60%. So it’s a key HIV-prevention tactic for Tanzania, where 1.5 million, or 4.6% of, adults age 15-49 are living with the virus.

Emanueli says he doesn’t have a sexual partner yet, so he’s okay with the required six-weeks abstinence period after the surgery.

After the informational session, nurse Nancy Nyangere Kedhahabi offers thorough HIV counseling. Photo by Josh Estey for IntraHealth International.

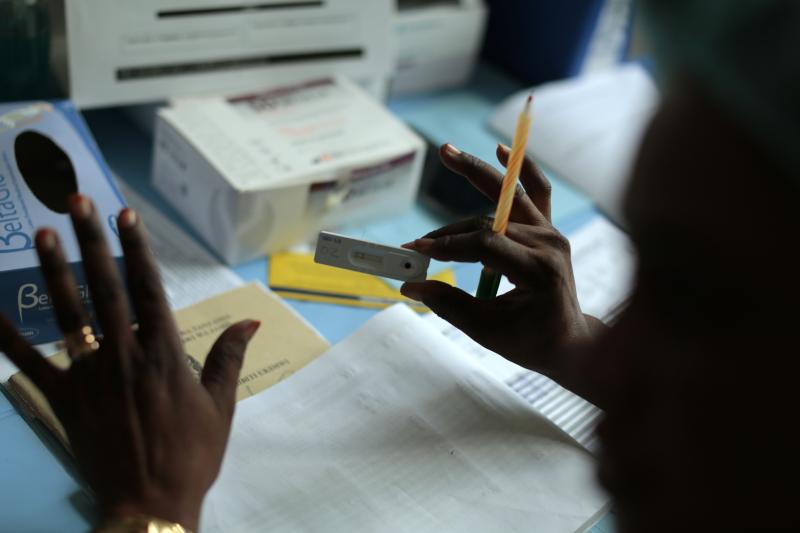

After counseling, clients get tested for HIV. Photo by Josh Estey for IntraHealth International.

After a few minutes clients receive their HIV test results. If a client tests positive, the nurse refers him for antiretroviral treatment. Photo by Josh Estey for IntraHealth International.

Nurse Flora gives 19-year-old Emanueli Somweli his test results. Photo by Josh Estey for IntraHealth International.

Previously only physicians and surgeons were qualified to provide VMMC in Tanzania. But Imelda learned to perform the circumcision surgery in 2015 as part of a health worker task-shifting and task sharing approach initiated in Tanzania by IntraHealth International and our partners to expand HIV-prevention services for men at greatest risk.

“Mwanza is the second-largest city, and the second-biggest region, in the country,” says Pius Masele, the regional AIDS control coordinator. “Mwanza’s HIV infection rate is 7.2%. We need programs like this to fight HIV, but we need more health workers trained to provide the service.”

There’s a big shortage of physicians and surgeons in Tanzania, so IntraHealth and our partners worked with the Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children to change policy and train nurses on VMMC.

Now hundreds of nurses in Tanzania can perform the procedure, which has greatly increased access to it.

The VMMC procedure requires two skilled health workers. Photo by Josh Estey for IntraHealth International.

Today nurse Imelda partners with Victoria Sitta, a clinician, to perform the surgery. Photo by Josh Estey for IntraHealth International.

Nurse Imelda is one of hundreds of nurses in Tanzania who are performing VMMC for HIV prevention. Photo by Josh Estey for IntraHealth International.

Around the world, 22 million nurses and 2 million midwives make up half the global health workforce. That means they are essential to national and global efforts to expand primary health care services and to achieve universal health coverage (UHC).

If we’re lucky, nurses and midwives are already present at every stage of our lives. To see us into the world and care for us as we depart it. To keep us healthy and protect us from diseases. To help us when we get sick.

Countries should tap into all the potential power of this workforce and allow nurses and midwives to work to their full potential. Health leaders need to offer them more opportunities and authority, which may, like in Tanzania, require changes to existing health care policy.

Nurses around the world have already shown they can learn advanced skills and take on more responsibilities that can lead us to UHC.

In Zambia, nurses heading up community health facilities are learning to lead frontline health worker teams through a Certificate in Leadership and Management Practice Program. Each nurse leads a community health improvement project and, as a result, their facilities have increased testing for HIV-exposed infants, antenatal care coverage, and the number of fully immunized children.

And in Namibia, nurses are initiating and managing antiretroviral therapy (ART). The previous policy required clients to see a physician for all ART services, which delayed services for many Namibians living with HIV. Now, nurses equipped with an ART certification are helping the country achieve its 90-90-90 goals. And the ratio of staff providing ART services is currently about 80% nurses and 20% doctors.

Post-operation, nurse Nancy Nyangere Kedhahabi explains to Charles Fita, a 40-year-old client, how to care for himself and avoid infection. Photo by Josh Estey for IntraHealth International.

Mwanza regional AIDS control coordinator, Dr. Pius Masale, explains that Mwanza is a key area in the country for VMMC and other HIV prevention tactics. “Mwanza is a trading center, with lots of new people coming through. The HIV infection rate is 7.2% in the region. We need programs like VMMC to control the HIV epidemic.” Photo by Josh Estey for IntraHealth International

Nurse Imelda wants more men, including those visiting the hospital for other reasons, to opt for VMMC.

“Right now, not enough people in the hospital get info about VMMC,” she says. “We need signboards, road signs even.

“I think adult men want the service, but don’t come in because of shame. They have to pass by other departments, like maternity, and feel shy being seen by women.”

Now ToharaPlus, a project led by IntraHealth and funded by PEPFAR through the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, conducts four-week campaigns around the country, and pulls trained health workers, including Imelda, on a rotation to work them.

“Men are more likely to come for VMMC when an outreach campaign is happening, even though the static site is right here,” Imelda says. “During campaigns, we get about 20 clients a day.”

Since 2010, more than one million clients have received VMMC services from skilled health workers, including 865 nurses trained by IntraHealth, through IntraHealth-supported outreach campaigns and static sites at facilities like Sekou Toure Regional Hospital.

“There was a 35-year-old man who I provided VMMC,” Imelda says. “He still contacts me to tell me how I helped him. He says I treated him very nice and gave him protection.”

This piece was originally published on the Frontline Health Workers Coalition Blog. IntraHealth’s Mary Goodluck Mndeme co-conducted interviews for this piece.

Get the latest updates from the blog and eNews