Where We Work

See our interactive map

Photo by Casey Bishopp.

For kids who live with the virus, an empathetic health worker can be a link to a lifetime of successful treatment.

“Can you see me?”

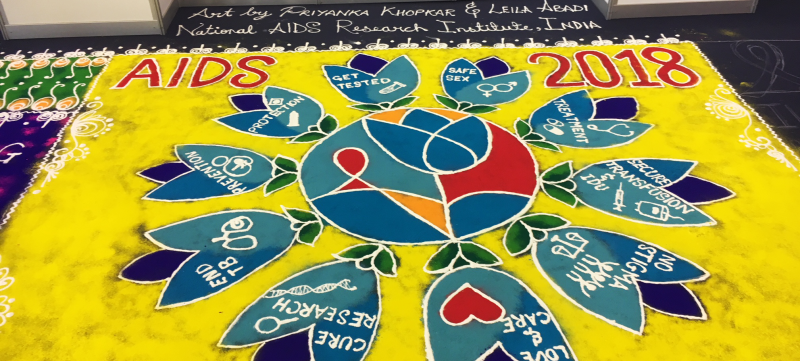

We heard this question repeatedly and in different ways throughout the week-long International AIDS Conference in Amsterdam this summer.

The question urged us to consider people who exist entirely at the margins of their societies, struggling for access to health care, for acknowledgement, for basic safety and health—people for whom this biannual gathering is possibly the only venue where they feel fully seen, safe, and prioritized.

For some of us, we’re still fighting for our basic human rights.

One attendee donned a cape made from two flags: the rainbow Pride flag, and that of her own country—Russia, a nation notorious for human rights violations against the LGBTQ community. She nodded politely as I told her about IntraHealth International’s work, and then she said: “For some of us, we’re still fighting for our basic human rights.”

Frankly, I was embarrassed. I was only just starting to fully understand that the reality for people who live with HIV goes far beyond having a medical condition, and coming to terms with how very little I knew about the lives of marginalized HIV-positive populations in general.

Nalugo Sharifah, a young Ugandan filmmaker, drove this point home in her documentary on HIV-positive youth in her home country, Crying for Third Line in Sub-Saharan Africa. It showcases interviews between young people living with HIV and health workers, the importance of adherence to antiretroviral therapies, and the need for greater availability of second- and third-line therapies. But it also includes gut-wrenching conversations with young people for whom the virus has advanced to AIDS. The interviewer explains that a sizeable portion of deaths due to AIDS in Uganda are among orphans.

It occurred to me: With no one to make sure they’re adhering to their drug therapies, to make sure they even have the drugs they need, how could these orphans be expected to stick to first- or even second-line therapies?

These children don’t have the agency, the ability to get themselves to a global conference to make themselves seen and heard. Yet they represent a huge part of the need for HIV services globally. And we’ve got to continue to find ways to reach them.

An empathetic health worker could be the difference between understanding and failing first-line therapy.

I couldn’t help but think that for these children, the difference between adhering to their treatment and failing first- or second-line therapy could lie with their first experiences in the health care system. For many young people, being able to talk about their HIV status, to ask questions in a safe and trustworthy place is key to accessing treatment and accountability.

Particularly for teens, whose brains are busy developing and dealing with all sorts of vulnerabilities, a responsive, open-minded, and supportive environment—an empathetic health worker—could be the difference between understanding how the disease works in their bodies and failing first-line therapy.

Health workers can’t provide more drugs or perform more procedures without the supplies and resources they need. But they can provide empathy and an unbiased ear. Like they have in Namibia, where local health workers partnered with IntraHealth to create teen clubs for HIV-positive youth. At club meetings, teens now find the supportive, informative environment they need to build good habits when it comes to managing the virus—keeping appointments, asking questions, and adhering to treatment.

Training frontline health workers in sensitivity and unbiased care from the beginning of their education can go a long way. Because combatting the epidemic and achieving the 90-90-90 goals takes more than scientific and medical breakthroughs—it also takes communication and frank discussions.

Linking social workers with clinical staff means a better care for HIV-positive children.

There was a loud call at AIDS 2018 for empowering churches, families, and community groups to be open with youth about sexual health issues. It seems like a natural piece of that strategy is empowering frontline health workers to do the same—especially for those orphans living with HIV, who don’t necessarily belong to a family or community group. Linking social workers with clinical staff means a more powerful approach to care for vulnerable HIV-positive children.

IntraHealth, in our work with 4Children, aims to strengthen the social service systems in countries where the disease burden is great, and link psychosocial services with clinical ones—linkages that have the potential to make a difference for young children like the ones in Nalugo’s documentary.

To all those kids and others like them who were not physically present at AIDS 2018: Yes, we can see you. Nurses, community health workers, and frontline caregivers see you. And we’re working to empower them to provide the stigma-free psychosocial support you need.

Get the latest updates from the blog and eNews